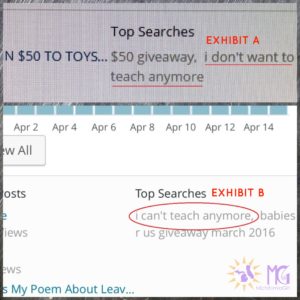

Today marks exactly one year without teaching. To acknowledge the occasion, let me take you behind the scenes of my blog and share the number one phrase — BY FAR — that brings people to my site:

I don’t want to teach anymore.

The proof. These phrases crop up every single time my “Top Searches” are refreshed.

A plethora of versions abound. Done being a teacher. Don’t want to teach. I can’t teach anymore. People punch these things into Google, and Google sends them here, because algorithms are strange, enigmatic beasts that I will never fully understand. These stressed-to-the-max, ready-to-quit educators keep finding their way to my blog, and it’s sort of weird because I’ve never written a post about that.

It’s time. It’s time to write a post about that.

In the twelve years I was a high school English teacher, I watched people leave the profession in droves. Some abandoned ship before they even boarded: a couple colleagues in my graduating class completed their student teaching, collected their college diploma, and promptly went back to school for an entirely different degree. Some hung in there for a handful of years before eventually succumbing to cynicism and fatigue. A precious few retired with a full career in their rearview — but, like Nancie Atwell, even they might advise the potential teachers of today to choose something else. The climate is different. The culture is different. The system is breaking, and educators are scattering to avoid the inevitable crushing debris when it all comes crumbling down.

I hope you will join the conversation.

I did not choose to leave — which means that maybe I didn’t have the cojones my Google searchers do, to look around and take stock of my situation and say, I’m done. To make my own decision. I let fate and a cross-country move make it for me, and there are a lot of incredible things about teaching that I really miss.

Actually, there are only two: my colleagues, and my kids.

They are the incredible things.

But everything else? I won’t go into detail about the budget cuts or the massive class sizes or the average salary, as that’s all been discussed ad nauseam. I’m not going to talk about the bone-deep exhaustion that comes from being onstage all day, or the drowning sensation that follows you home on nights and weekends when you have hundreds of papers to grade.

These are the other things — the stuff you might only understand if you have a key to the teachers’ lounge.

1. You are an “authority figure” with no real authority.

A friend once told me, “You have no idea what it’s like to have a real job — something with deadlines and adults breathing down your neck. You get to be your own boss.” The sheer ignorance of her declaration has stuck with me for years, and still needles me — mostly because that line of thinking is an extremely common misconception.

When we close our door each day and stride to the front of the classroom, it’s easy to fall prey to the illusion that we are in charge. It’s your name on that door, after all, so you must be the boss.

Reality check: you are not the boss.

Parents are the boss of you. The administration is the boss of you. Common Core is the boss of you. The students can sense it, which occasionally leads to comments like, “My parents pay your salary, you know.” Truth. And because of that truth, there is often immense pressure to compromise your integrity: to pass a child who has not demonstrated mastery, to allow an extension on a paper you assigned two months ago, to give less homework or different projects or more lenient grades, because sometimes you are expected to avoid rocking the boat.

2. Your day does not resemble that of a typical white-collar professional.

Despite my aforementioned friend’s ignorance, I’ll give her this: sometimes you are painfully aware that your “real job” does seem suspiciously different from other “real jobs” which require a college degree.

Here are the things your friends can do at work:

1. Pee

2. Get coffee

3. Spend fifteen minutes chatting leisurely with a colleague

4. Go out to lunch

5. Complete paperwork and other job-related tasks during the actual work day

6. Sit down occasionally

I’m pretty sure the real reason summer break exists is because the School Gods counted up all the seconds you don’t get to use the bathroom and handed them back to you in one big chunk. Twenty-five-minute lunches are not conducive to nice, relaxing meals beyond the building’s walls, and you can only relieve yourself during passing time — which, unfortunately, is the only opportunity all the OTHER teachers have to take care of business.

Because you know what else is the boss of you? The bell schedule.

3. Everyone thinks they know how to do your job. EVERYONE.

Adding to the sting of your not-in-charge-ness, many people who ARE in charge have literally never taught a day in their lives — and a lot of them are pretty sure they know how to do it better than you.

Most people have lights in their home, but that doesn’t make them electricians. My husband doesn’t know how to manage a restaurant just because we’ve gone out to eat. Can I profess to be an expert on successful lawyering because I watch Law & Order: SVU once a week?

Surely, teaching is different, though, right? At some point, just about everyone has sat in a classroom. We were students, after all. We watched our teachers — some we loved, some not so much — and because of that lengthy, multi-year observation we assume we know what they do for a living, because we sat in a classroom for years and years and years, and we watched them, and that must be enough research. Six, seven, eight hours a day, ever since preschool, everyone has seen this job, so everyone is allowed to have an opinion.

But even brand new teachers can tell: the view looks a whole lot different from behind the podium. So when your high, high, highest-ups are committees of people who only know what it’s like to be a student, it feels akin to a team of accountants trying to wire a building.

You know what’s probably going to happen? That sucker’s going up in flames.

4. You wanted to foster imagination, not slaughter it.

For a while now, teachers have been battling an increasing pressure to “teach to the test.” Despite our banshee-esque warning cries, this situation is not improving. Courses with “real-world” value (home economics, for example, or shop class) are dying a not-so-gradual death, as there is no “Foods & Nutrition” section on the SAT. Art and music programs are still in grave danger — and, in some districts, have already been slashed to ribbons.

An elementary school teacher I know — who is a part of one of the wealthiest, most reputable districts in her state — attended a recent meeting where staff members were instructed to “drastically limit or entirely eliminate” story time. “It’s not differentiated enough,” they were told, “and therefore is a waste of valuable class time.” THE KIDS ARE IN THIRD GRADE. They deserve to gather around a rocking chair and feed their imaginations. They deserve the magic of a captivating story. They deserve to learn that you can read for pleasure instead of strictly for information.

“Core” high school classes aren’t immune to the damage, either. Elsewhere, in an entirely different part of the country, a ninth-grade teacher-friend of mine was asked to abandon any educational math games and “make more of an effort to spoon-feed, please.” English teachers look on helplessly as more and more works of fiction are plucked from the curriculum and replaced by fact-driven nonfiction. Even though we’re sometimes invited to join curriculum committees (as I did) under the guise that we might have a say, it’s ultimately just a ruse: we have only as much freedom as our national and state standards allow. At the moment, there is a relentless push toward FACTS. DATA. STATISTICS.

That doesn’t leave very much room for make-believe.

But here’s the thing: discussions about fiction lead to rich discussions about life, which drives something much more important than the growth of a student — it guides the growth of a human being.

5. The technology obsession is making you CRAZY.

Our beloved works of fiction aren’t just getting elbowed aside by facts and figures. They’re also being trounced by the frenetic crush of technology. “The children must learn ALL THE TECH!” everyone shouts, flailing their arms and stampeding toward the nearest Apple store. “It is the way of the future!”

Then why are some big-shot technology CEOs sending their kids to computer-free Waldorf Schools? There’s an app — er, a reason — for that.

This one is tricky. OF COURSE, as teachers, our job is to adapt to the changing times. But I might argue that our job is also to challenge our students with something new — and, to this generation, technology is not new. In fact, it is all they know. Our kids don’t need more of it — most of them have been swiping and zooming and smartphone-ing since they were toddlers — and they continue to do it right in the middle of your (probably fact-driven) lecture about some (probably nonfiction) book, by the way. It’s incredibly frustrating when all that glorious innovation serves as more of a distraction than a learning tool.

I’m not trying to get all Yeah, well, back in MY day… on you. But, um, back in my day — look, even a decade ago — it felt a little simpler to practice using something TRULY innovative: our brains. That ability is disappearing, in large part because technology has eliminated the need to wonder.

One of my favorite lessons to teach involved a set of four philosophical questions. I typed them up and distributed them to my sophomores, who were allowed to work in groups.

2006: The students wondered about the answers, pondered the possibilities together, bounced ideas back and forth.

2015: The students said, “I’ll Google it.”

“No,” I said. “This is a Google-less assignment. You need to THINK.” They stared at me, agape, and in a mild state of panic.

They grumbled, but then they put the technology away, and they turned to their peers, and they wondered.

Though we teachers tend to stick together, I also have a group of friends and family with a wide range of careers — they run the gamut from successful marketers to mechanical engineers to human resource managers. All of them have interviewed prospective employees for over a decade, and all of them now have a similar complaint: it’s becoming close to impossible to find candidates they actually want to hire.

The three C’s people suddenly seem to be missing? Curiosity, creativity, and communication skills.

Technology is wonderful — nay, necessary — for a plethora of things, but it’s killing those beautiful C’s. And as a teacher, you don’t just witness the death, you are expected to assist in the murder. Because of standardized expectations, you must incorporate more and more tech, even when all you want to do is take a hammer to anything with a screen.

6. All the entitlement and the trophies and the apathy and whatever.

The air inside your classroom walls is probably thick with the stench of “It’s not my fault, it’s your fault,” and it sure seems like the smell is coming from the students.

Ironically, this is not their fault.

Like cigarette smoke, it gets carried in from home, rising from their backpacks, woven through the threads of their clothes and the fibers of their upbringing. Their whole lives, they have received copious awards and accolades just for playing — NOT for excelling — so it’s no wonder kids have come to expect an A “because I tried.” But sometimes a D paper is just a D, which doesn’t necessarily mean that Johnny has an evil teacher. It means that Johnny might have actually earned a D this time. It means he might not have written a perfect paper. It means he needs to stop waiting until THE VERY LAST SECOND to start an essay he’s known about for three weeks.

But Johnny doesn’t know it means all that, because what he hears at the dinner table is that his parents are UNBELIEVABLY ANGRY that his teacher had the nerve — the nerve! — to give their baby a D. (Brace yourself for the irate phone call in the morning.)

Of course, for every helicopter parent, there is a devastatingly absentee parent, as well as an equal number who are so remarkably supportive that you wonder if they’re even real. They are warm and generous and responsible. You tell them at conferences, You are REALLY doing something right, and you mean it.

I hope I will be that kind of parent.

I became a mother a few years ago, and I must shamefully admit I get it now. My children ARE special. My children DO try. I do not EVER want them to feel like they are anything less than the most important people in the world. When my daughter’s preschool note tells me she was not a good listener that day, I feel frustrated and helpless and a little bit sure the teacher is just being too demanding. When she ran her first Toddler Turkey Trot last November, the people in charge asked if I wanted to buy her a medal. “Um, obviously,” I said. “She will obviously, absolutely get a medal.” Without hesitation, I forked over my money and contributed to the Trophy Generation Fund.

As a parent, I understand.

But as a teacher, this is what you wish you could say: Stop making excuses for your kids. STOP IT. Teach them to earn things, not demand things. Hold them to a higher standard. Challenge them. That way, when I try to challenge them, they’ll know we both expect it.

They’ll know we are on the same team.

Left to their own devices, the kids will be the first to tell you: Yeah, I totally forgot about that assignment. I didn’t really try my best. I just didn’t feel like finishing the reading. Whoops — sorry, Ms. B! They’ll cringe at you with raised eyebrows and endearing self-awareness. They nod emphatically when you analyze the apropos theme of “Harrison Bergeron,” and they laugh uproariously when you pull a pretend trophy from your desk and give it a quick shine as soon as they catch themselves in the act of whining.

They know. Deep down, they know exactly what’s going on. They are smarter than that, and they are capable of more failures — and consequently, more successes — than the world is allowing them to experience.

7. There is no reliable way to assess who is ACTUALLY good at this.

If you’re a teacher worth your salt, this might be the most troubling of the bunch.

In order for people to really know how well you’re doing your job, they have to watch you do it. But when there is only one administrator for every thirty-plus teachers, adequate observation time is often a physical impossibility. Even if an administrator’s ONLY JOB was to sit in classroom after classroom, there would still be too few hours in the day — and principals and assistant principals are responsible for a lot more than staff assessments. Between the scheduling and standardized-test-organizing and discipline issues and parent phone calls and endless on- and off-campus meetings, sometimes even a ten-minute walk-through is an achievement.

Not to mention the embarrassing issue of content area expertise: how can an administrator with a history degree assess whether or not a physics teacher is delivering accurate information? How can an assistant principal with a science background critique an English teacher’s lessons about sentence structure?

Depending upon your state and your years of experience, you might be observed anywhere from once a month to once every couple of years. Who knows what magic is happening in your classroom all those other days? So in the meantime, lawmakers and district higher-ups are scrambling to figure out a way to fill in the blanks.

A popular bright idea is to examine students’ test scores. In theory, this should work — but in practice, you’ve got to be kidding. Students are not products tumbling off a cookie-cutter assembly line. They are human beings, and there are thirty-five of them per class period, and they are influenced by FAR more than yesterday’s vocabulary lesson. You are not in charge of how well they slept, or the breakup that happened last week, or if their family has enough money for breakfast — but all of those things affect test scores. So do IEPs, 504 plans, and whether or not you are teaching an AP or Honors class filled with students who might perform well with or without your help.

As more and more districts begin to adopt this nonsensical practice, who will teach the kids who are struggling? Which educators will potentially sacrifice their own careers to guide the students who work hard for a D+? Some of the very best teachers do that now, with only intrinsic motivation working to retain them.

Another method is to place the burden of proof upon the teacher. Each year, there is a different set of goals to accomplish — some you set yourself, and some that have almost nothing to do with your specific classroom environment — and it is up to you to prove you’ve met them.

So instead of spending your prep hour — or your Sunday night — creating a brilliant lesson plan or grading the ten dozen essays you just collected, you must spend that time figuring out how to meet arbitrary goals and initiatives that will become irrelevant and obsolete by the following school year. After that, you must waste utilize class time implementing said goals and initiatives, and then you must spend more prep time and Sunday nights writing reports to prove how well you implemented them. That, combined with your students’ test scores, shall determine whether or not you are an effective educator.

Can I please just talk about Of Mice and Men instead? Can we spend that time learning why some words on a page just made us cry a little bit? That’s the important stuff. That’s what matters. Those are the things that teach us who we are.

Here are the other things that matter: Helping a group of students work through a disagreement civilly. Keeping everyone calm when someone vomits on the floor. Watching the shyest student in your class, the one who never ever spoke back in September, volunteer to read a part in The Crucible — and he’s hilarious, and he does it with an accent, and he makes two new friends because he finally let himself be vulnerable.

Your job is so much more than test scores, meaningless goals, and cyclical initiatives. It is tying shoelaces and distributing Band-Aids. It is listening to a parent cry about her crumbling marriage. It is showing teenagers how to debate thoughtfully, how to think critically, how to disagree respectfully. It is hearing from students ten years after graduation, because they just thought you should know it was your Spanish class that made them want to study abroad, your passion for science that led to a major in biochemistry, your quiet encouragement during their dark days that convinced them to keep coming to school in the first place.

Where does that fall on the “Highly Effective” checklist? How can you document that kind of delayed impact? It certainly can’t be measured by A’s and E’s, or even by weekly walk-throughs. It’s no wonder you’re getting frustrated.

It’s no wonder you don’t want to do this anymore.

But if these are the reasons you might leave, here is the reason you might stay: the kids, man. The kids. After a year without them, you might miss their unbridled school spirit during Homecoming Week, their contagious sense of humor, the way they draw pictures for you and wave joyous hellos in the hallways. You might miss their ability to make you forget about the rough start to your morning, or the looks of awe on their captivated faces when they finally learn something that matters.

If it weren’t for them, instead of Googling “I don’t want to teach anymore,” you might already be gone.

Can I PLEASE talk about …?

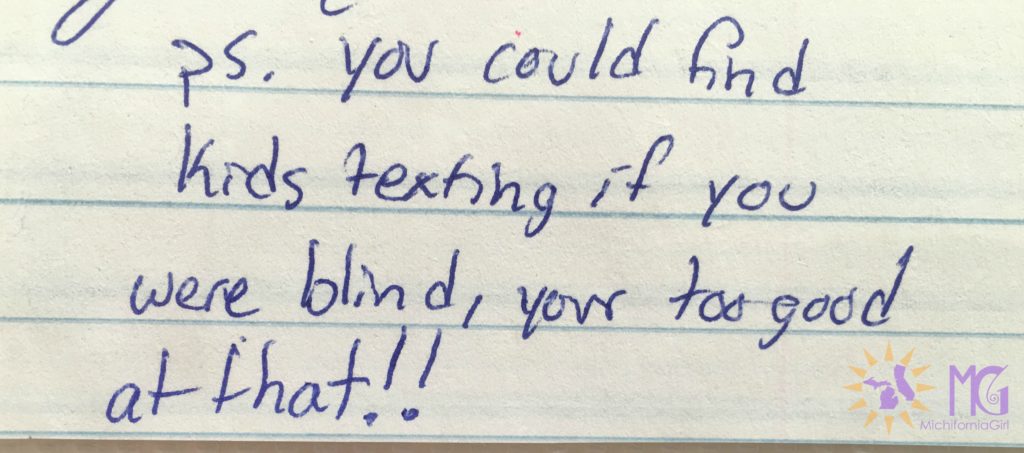

I remember you saying that at lunch! Lol

How I miss those conversations!

Awesome article! I was up at 3am thinking about work today and stumbled across this … all 7 are spot on.

It’s 2:30 am and I just finished writing my individualized smart goals that have to be changed every two weeks, and directly linked to the STAR exam we are now giving every 6 weeks. I will be writing my new four part rubric for all 5subjects and doing my atlas protocol which summarizes all the standards assessed in the star and how I will differentiate and improve scores for each student. In addition, I have to change my bulletin boards and add authentic rigorous student work with individualized goals, rubrics, I can statements that are all level four on the danielson wheel and contain I can ……by doing x y and z. In addition, all student work must have one positive and one critical note attached for each student. My students are questioned by administrators about their smart goals, the level they are on depending on the star and what they need to do to improve. My students are kindergarten kids. They are not allowed to draw other than to respond to questions and are expected to read non fiction and respond to comprehension questions. I feel exhausted and some days I feel so sorry when I look at these little faces that are so tired and frustrated. Five year olds forced to understand that they are in the low group because they can’t read fluently and they can improve by reading more…..when in actuality they are developmentally not able to meet some of these standards without yelling and punishing and forcing. it’s noy why I got into teaching . I hate what we’re doing to these kids. Most of the work I’m required to do has nothing to do with them and everything to do with jumping thru hoops for disconnected idiots who have no clue how to teach or how children learn. Sorry… your words just touched this dormant monster of discontent.

Soul destroying and tragically realistic post. Our poor kids.

EXACTLY! Same here!

So sad. I am currently in my 12th and last year of teaching. I used to be able to shape my own instruction to my student needs. For the last few years, all elementary teachers in my corporation have been forced into scripted teaching. My kids used to make so much progress. They would make 2-3 years of growth because I challenged them daily and created a very rigorous program for each of my first graders on their own level. Now I have been reduced to robotically reading my script for both reading and math. The scripted curriculum even details what the children should say in response. When I’m not script reading, the kids are on corporation mandated technology programs for the rest of the day. I’m done. I feel sorry for the little ones, but I can’t do this anymore.

After 30 years of teaching at public elementary schools in Broward County, Florida, I retired in June of 2023. That was 5 months ago. I could have stayed on and entered the Drop program and earned a much higher pension. This would have helped financially, but not mentally. I was fried. I half-assed my last year and finally crawled over the finish line. I am now so grateful that I’ll never have to: grade another paper, justify another innocuous action, sit through another meaningless faculty meeting, follow another counter-productive directive. Public education in the United States is a sinking ship. I’m glad I made it to shore before it sunk below the waves.

Once again…. NAILED IT!!!! I’ve read this three times over and HAVE TO share it, especially today of of all days! Keep the blog posts comin Melissa, you have me entranced!

Thank you so much, Kelly! I really appreciate the share! 🙂

Hello Mrs. Bowers,

I don’t know if you remember me but my name is Samantha Hindle and I had you as a teacher. I must say this is an amazing and funny blog. Coming from a students perspective, I understand the life of a teacher more, and it must have rough but I’m glad you stayed as long as you did because I would have missed out. And thank you for staying for all your reasons. You made high school more fun everyday. I hope your career is a complete success.

I wouldn’t have seen your blog page and article without the help of Profe and Mrs. Crow. So thank you to both of you!

Of COURSE I remember you, Sam! Don’t be silly. 🙂 And it definitely wasn’t “rough” — it was AWESOME, because you guys made it awesome. I hope that came across in the post. If we hadn’t moved, I would still be there. I miss it every single day.

I hope things are going well! I’m sure you’re doing wonderful things. So nice to hear from you, and please keep in touch!

Melissa,

Happened across this article of yours! What you say is so, so accurate. Teachers really do have no authority, everybody does think they can do your job, kids are too often praised and elevated just for existing (this is really one of my pet peeves!), technology has become the mind-numbing thief of imagination, and in no way does your day resemble that of any other college-educated, white-collar worker. That being said, teachers hold so much influence, I believe, over kids’ development. Everybody remembers their favorite teacher — and they can tell you why! I’m happy to see that you have saved your notes. I, too, have saved notes/ letters from my students. After retiring, I discarded almost everything from my teaching days. Everything except my well-marked Senior English text and the notes from my students and, later, teachers. You were such a good teacher!( Though I realize that comment may not mean much, considering reason #7 :)) I remember enjoying every visit to your classroom. Hope to see you in the movies someday soon.

How wonderful to hear from you, Joyce! Your kind words mean a lot, naturally, and I enjoyed your visits, too. You were never afraid to participate (which was always entertaining for the students), and your thoughtful feedback helped me to become a stronger professional. We always remembered you fondly! I hope you’re enjoying retirement. What a full, beautiful career you had — you certainly deserve rest, relaxation, and some good wine. 🙂

Three more years until this English teacher can retire with 30 years. Time for bouncing creative ideas off colleagues is a thing of the past. Data. I don’t teach data; I teach kids. Unfortunately, I am limping rather than inspiring.

You hit the nail on the head, and with amazing wit and insight. Interesting that you barely mention the summers off . . .except for the ability to pee when you want . . . and so many people think that teachers are there for the summers. They forget that’s when we go to school, change lessons, write curriculum, etc. You’re so good at this MB, but I’ll bet there’s a classroom in Cali just screaming for your presence!! Miss you.

So nice of you, Shawn. I’ve considered trying to get licensed out here (there would be extra coursework, etc.), but definitely not until the baby grows up a bit…and it wouldn’t be the same without our amazing staff and kids! Miss you all so much. I hope you enjoyed the first year in your new role! You’ll be moving up quickly, I’m sure.

This should be required reading for every legislator in Lansing and in every other state Capitol. Well done, well done. I’m a recently retired elementary teacher who could have taught a few more years but decided I’d had enough. I still sub in my old school because like you, I miss the kids and the co-workers. It is crazy the direction education has taken, and so sad. You speak for every frustrated teacher out there. I have seen the dramatic swings over the years in the vastly different approaches to teaching and the pendulum never seems to rest in one direction for very long. We can only hope that wiser and more knowledgeable heads making the decisions will prevail. Thank you for a spot on analysis of the state of the classroom.

Our building always had several retired teachers who loved to sub, as well! Thanks for such an insightful comment, Brenda — especially love the part about the pendulum. So true.

Just posted on my Facebook! :MUST SHARE. MUST READ. MUST COMMENT. Wow, so much to say. I teach art (and coached basketball) and am unhappy! This blog says/explains it all. Amazing effort. I’m a slow reader and took the time. You can too! Must be shared with our administration. THIS is a PD day!!! This is the article. This demands a response.

Wow! What an awesome compliment, Jeremy. Thank you, thank you, thank you for the share!

The part about the arbitrary data collection for some nameless Lansing ‘educational leader’ is spot on!

That data collection sure is somethin’. Thank you for reading, Susan!

Amazing! You nailed it!

I recently left teaching after only 4 years.

Thanks, Tiffany! Best of luck in whatever comes next for you. 🙂

Can you add, Administrators failing to do their jobs and pushing it back on the teachers.

Yikes! Administrators can certainly make a difference in the direction of your day — and on a larger scale, the direction of your career. Curious to know a bit more about your experience, and I hope that situation improves for you!

So true, send out a distruptive, rude student only to have them back in 10 minutes.

I loved this article, read it on a FB post twice, commented on it, then found out from your mom who you are… You were a student in my second grade class a “few” years ago!! I love how you have captured the frustrations of teaching as it has evolved in the past 10 years or so, and am so proud of ( but not surprised!) the succinct and intelligent writer you have become. Wow! I want to read more of your posts/blogs/articles!

Thank you, Mrs. Campbell! I remember being “the new kid” in your class — moving is tough, and I’ve always appreciated how welcoming you were during that transition. Great to hear from you, and thanks again for your kind words!

My daughter taught middle school and high school English for 7 years. She was enthusiastic, active in her school and district and loved her work. She worked in Missouri, which pays its teachers very poorly. I was paying her student loans for her and half of her mortgage payment on the townhouse that I made the down payment and closing costs for her. As a single woman she simply could not afford to teach. Sadly, she had to resign and go to work in the private sector. Such a sad commentary on the lack of support our society accords teachers and the education of this nation’s children.

It’s such a shame when energetic, enthusiastic teachers are not able to continue. She’s very fortunate to have had your help! I hope she’s found joy in her new career, though I totally understand that there is nothing quite like teaching.

Hi Mrs. Bowers,

Not sure if you’ll remember me, but I had you in 10th grade. I found this article to be incredibly well-written and it echoes the feelings of the handful of teachers I know.

After reading it, I felt like I needed to come here and write that I’m sorry to hear you’re not teaching anymore because it means that there are hundreds of students throughout the next 25-ish years that won’t be lucky enough to have you as a teacher. While my career (mathematics) has very little to do with English, writing, or grammar, I recognize that you were one of the best teachers I had in high school. It is often said that the teacher makes the class, and it certainly rings true in your case. Thanks for caring about your students, and thank you for being a positive influence on me as a high school student who probably didn’t always try as hard as I should have in English class.

Well, that just made my whole weekend (and made me tear up). Of course I remember you, Jake! That kind of sparkling personality is impossible to forget. I think someone told me you ended up at U of M — so, so proud of you, fellow Wolverine! 🙂

As a teacher at an independent progressive school, I relate to many things in your blog. Though I do not have to follow the Common Core or state standards, those expectations are entering our school environment. I’ve been at my school 10 years and we’ve shifted from many hands on experiences and projects to now having to focus more on essays and students proving their ideas in writing. The students also have less respect towards teachers as they are supported by parents and administration. It makes me sad how things are changing – and have heard the same from my friends in other independent schools . The kids are great and I will miss them when I leave. I’ve been contemplating a move out of teaching for awhile.

It’s so interesting to hear that people in your position are experiencing some of the same demands. What are you planning to do if/when you leave? I know one of the most frustrating things for some teachers is that they’re not sure what else to do with a degree in education.

What a moving and accurate account of what is going on in education today. I have been teaching for 17 years and turned my resignation in last week. My passion for teaching has faded away for all the reasons you mentioned. Staying for the kids is what I did for the last 5 years. Unfortunately, all the other issues shadowed over my ability to continue to be a good teacher.

I am fortunate that I have the ability to devote more time to my husband, children and grandchildren. I pray for my dedicated teacher friends and wish them the best through the ever changing educational system.

Thank you for your honest and accurate works.

Thank you so much for reading, Deb. I wish you the best in this next stage. Enjoy all those precious moments with your family!

A very important article. Thank you for writing it.

I quit teaching in 1994 in South Africa after a 17-year career as a science & math teacher. It was one of the saddest days of my life, losing an entire career that I had worked so hard at. I did my teacher training in London at an incredibly rough school, lots of violence against teachers, and I often wonder why I didn’t quit right at the beginning.

What you say is very true, and very sad. But I have told everyone I know, don’t go into teaching, it’s not a proper profession any more. I am now in the small country of Swaziland, where the schooling is based on the British system and is not so bad as the “outcomes-based education” they tried in South Africa, with disastrous results. I do a little tutoring for home-schooled students & I find it very rewarding. But I edit scientific manuscripts for a living now, and I’ve promised myself I will not end up in the classroom on a full-time basis again. It does feel so good when you stop hitting your head against a brick wall.

Wow! Amazing to hear from someone outside of the U.S. educational system. I’m totally fascinated.

Thank you for sharing your experience! I know leaving after 17 years must have been incredibly difficult. I appreciate your comment, your kindness, and your readership!

I started teaching when I was 45. Going back to college to get a Master’s and teaching certificate was scary, but I had been substitute teaching for several months and knew I wanted it. I loved it at first. However, all that you blogged today is what I encountered. I have been blessed with the “come backs” who tell me what my class meant to them, what I meant to them. I first taught students incarcerated, then elementary school. Some of my second graders, now adults, tell me that they loved that my plants had names and so on.

The “come backs” make everything worth it. 🙂 They just reinforce the fact that, despite some frustrations, what you are doing is often incredibly impactful.

Melissa,

I’m writing a book covering a ton of the history of computers in education, going way way WAY way back to the very beginning, 1960, and then even before that with Skinner and teaching machines.

I’m always interested in hearing about the teacher’s plight today, about teachers leaving the profession and why, and in particular, about their experiences with technology in the schools (how much they did the teacher embrace and how much was forced down from the school, from vendors, and/or the school district).

Would love to learn more about your #5 above, about how the obsession with technology makes you “CRAZY.” I can totally see that. And it’s nothing new. And yet, oddly, it’s been kind of the same hype for 55+ years. Would love to see you write a more detailed blog post about it some time. Or, email me if you have a moment. Am always looking for more insights from real teachers who’ve been in the trenches.

It’s because school districts and administrative types always fall for the junk tech and applications that are poorly designed and implemented. Also hardware is usually not replaced in a timely way.

Sounds like an interesting concept for a book, Brian! I’d have to agree with Francesca: it’s more about a misapplication of what could be an asset, and a serious lack of time/funding for training.

That, and the hourly battle that is cell phones. They are ALWAYS, always out — it’s like an extra appendage. Sometimes the kids don’t even realize they’re glued to them.

All so true!

I can really relate to so much of this. As the Digital Teacher Librarian I see so much spent on technology and I always feel conflicted. On one hand we need kids know how to really use technology and on the other it is a huge beast that feeds on the resources at a level never seen before. Most people are afraid to call it out — thanks for doing that!

Totally agree! I know our media specialist really worked hard to find beneficial technology-based lessons the kids could try. I understand the internal battle!

This is a powerful first-hand, in-the-trenches account that people like Arne Duncan would be wise to read! Thank you Ms. Bowers. Please don’t give up on teaching — we need people with your passion! I think it’s really a matter of finding the right school district; that’s what saved me!

Thank you, Matthew! You’re absolutely right: the district can make all the difference. I loved mine, as well. Truly. If we hadn’t moved across the country, I’d still be there. I’m glad you wound up somewhere so wonderful!

I’m finishing up my 37th year of teaching at the elementary level; 7 years as a bilingual teacher in California and 30 years in Michigan. What a ride! I tell people who ask that I am contemplating retirement, but I still enjoy being in the classroom. I decided two years ago (after receiving my first lousy evaluation based on the new state requirements) that I was going to do what I was hired to do….TEACH! I jump through the required hoops, but I went into teaching to teach kids, not to please legislators. Your article was spot on. Thanks for sharing what teachers are truly feeling. Say hi to California for me and eat an In-n-Out burger for me. 🙂

Another California/Michigan resident! And 37 years! Amazing. It’s incredible to think of all the lives you’ve affected throughout your career.

And now…off to indulge in some Animal Fries. Good call.

Did you not understand all the above complaints before choosing to become a teacher? You chose this profession, don’t like it, Quit.

Sorry, but did you read the article? No, the teachers don’t understand the complaints before they start. And, yes, they DO quit. This quitting chaos is becoming a huge issue for our future generations. Just like the article said, guess it’s hard to understand unless you’re the one behind the podium.

Amazing. I mean, really amazing. I am sharing this with so many colleagues immediately!

Thank you, friend!

Julie! Thank you so much for sharing! I love all the new pics of your little man. He’s so sweet.

Eerie how when I passed this on to friends, they thought it was me. Here is why…

1. Left the classroom almost exactly one year ago after 15 years of teaching English

2. Moved across the country (from AZ to IL)

3. Have a four year old son

4. Blog that sounds “just like you talk to me”

Thank you for showing people that our struggle is real, real frustrating. The public hears “teacher” and scoff because they think: union, tenure, and tests. When will people understand that attacking the soul of the community that nurtures children into morally-conscientious adults results in opiod abuse due to national depression , intergenerational poverty due to poor local budgeting, and a generation of apathetic hate-mongers due to the discontinuation of critical thought? Aargh! You get it. Thank you.

Well, hello, Life Twin! Your blog is great. I love the “Spark Note Summary” at the end of your posts. Written like a true (ex-) teacher.

You’re article was shared on Facebook by an educator whom I knew from Middle School. I did not have any of his classes but I knew who he was. I was a difficult student. I don’t want to table any more than that here. I am 56 now. Although I never ascended to lofty heights in business of government I have had a fulfilling life thus far. To be short, you’re article made me cry. I often think back to the educators who, despite my best efforts, instilled the tools that has made my life comfortable. I dropped out at 17, enlisted in the Navy, worked a series of low skill labor jobs. Eventually started a small business. Became involved with local government and social interests. Nobody that special, but. Had not those dedicated educators grit their teeth and persisted and worked so very hard to make their classes interesting I don’t know where I would be now. Behind bars perhaps. So I apologize here to all those teachers I have not been able to contact in person for my behavior in your classes. You got through, I paid more attention than I would have you believe. Your efforts were worthwhile, for me anyway. I understand the many, many reasons to leave this profession but please consider the many, many more young people like I was. I know this doesn’t add to the paycheck or make the job easier. Thank You teachers…

I found this comment so incredibly moving, Peter, and you weren’t even my student. It’s everything we always hope to hear: that something about your time in school affected your life in a positive way — and in your case, it sounds as if it was remarkably profound. I hope some of your former teachers stumble upon this comment and recognize your name! What a beautiful testament.

This is the biggest bunch of BS from a person with cry baby Union mentality! Suck it up butter cup! You only work 8 months out of the year with above avg. pay and benefits that any private sector employee would die for!!

I’m sorry to hear that people in your life taught you to “quit if you don’t like it.” I don’t think that is a very healthy lesson to learn as life will often have difficulties, and some are worth pointing out as a means to starting change. There are countless examples of people “complaining” about an implemented system, and that system changing for the better. In fact, I would wager that your life is better due to people who didn’t “quit because they didn’t like something.” They pointed it out and pushed for change. Think hard and I bet you can find examples.

Or perhaps, you are saying that the education system is perfect, and there is absolutely no reason to even consider otherwise. If that is your stance, I would encourage you to do what a former teacher may have encouraged you to do … read, read, and read some more. I think if you read with an open mind, you will see that there are large issues.

And lastly, educators work 9 months per year, and get paid for 9 months per year. It is not some scam where they get 4 paid months off.

I really am curious why you don’t take your own advice and “suck it up butter cup”, get a teaching degree, and get this cush job that everybody would die to have. What’s stopping you?!

This was my Facebook post when sharing your great piece of writing:

“It is showing teenagers how to debate thoughtfully, how to think critically, how to disagree respectfully.”

Comments like these make me wonder what it will be like for American teachers if there is a President Trump in the White House! ? It was hard enough having a teaching career during the 3 decades after the Watergate scandal, when respect for authority plummeted! This excellent piece of writing illuminates why being a school teacher was by far the hardest job that I ever had–except, perhaps, for being a parent of three!

#NotForTheFaintOfHeart

#ButItDoesHaveItsImmeasurableRewards!

Bless you, Melissa, in your newfound writing career! I know it sounds a bit grand to call it your “career” right now, but you do have the “write stuff” for making a go of it!! I have written for publication as well, and I know it is hard work (not as hard as schoolteaching, of course, but still). Anyway, keep it up!

(Oh, and you should be teaching education at a local college–even part time! If you could somehow make that happen, it could have an incredible impact on a great number of future educators. Just sayin’!)

All the best,

–@northernlarry 🙂

Thank you so much for your encouragement, Larry! Your hashtags cracked me up. I would LOVE to teach education at the college level, actually — perhaps when my youngest is a bit older, I’ll look in to it. I appreciate your Facebook share!

I’d like to add that it is very hard to email during the day! Most people spend half their day dealing with email and responding….we all spend half of our evening catching up with it!

I also hate the “youtube can teach me” ideal parents and students have developed. It’s so much easier to actually pay attention and ask me questions in class versus trying to let someone reteach it to you (sometimes wrong) on the internet. If video learning worked, teachers wouldn’t be in the classroom anymore!

I worked for 10 years in corporate America and transitioned to teaching. It is NOT what you think it is. I’ve never had a job where I was so busy during the day…and teaching never stops. You go home and plan and grade…and take required training…and plan for student extracurriculars you sponsor…and read articles for the teacher STEM program they signed you up for…and wake up at 3 am thinking, how can I deal with these 3 students who are behind tomorrow (and then realize you have to be awake in an hour and a half so you might as well just stay up). It NEVER stops…the hours I put in are longer in the school year (oh I also plan during the summer and have meetings too) than I had in a 65-80 hour a week corporate job.

The virtual teacher trend is so scary, isn’t it? Nothing can replace the experience of being physically present in a classroom and engaging in discussion with one’s peers.

What a fascinating perspective you have, as you worked 10 years in corporate America first! The general public needs to hear more from people like you.

Melissa, I just read your article on The Huffington Post on this topic. It is SO good. Everyone needs to read it. As a former teacher, I understand everything you wrote and agree completely with you. I have written some of the same things on my website, SmartHelpForStudents. I hope the teachers and parents who read your blog will check out my website, too.

Janice

Melissa,

Thanks for this. I was a teacher for 10 yrs. and since then I have been working for 15 yrs in corporate foundations, international development, technology and stuff. I have always said that I would go back to the classroom some day. I think that being a teacher is what I am best at. Mostly I have been making it up over the last 15 years. It’s totally possible to do that out here with these “real jobs” (especially if you’re white and male.) The one thing a good teacher must be (from my humble perspective) is authentic. That’s mostly frowned upon out here in real job land.

However, I also now know that teachers rock. When I have been able to hire staff I always look for teachers. The ultimate generalists with VERY steep learning curves.

Now (don’t tell anyone) I am actually looking in to going back to the classroom. I’ve learned something out here in real-job land. I’ve learned how to know what I don’t have to care about. And I’m old now, so that helps. I miss the kids. (I was actually in a “business mtg” the other day with a former student of mine. He was brilliant and I took complete credit for his brilliance!) Maybe I won’t do it. Maybe I’ll keep pretending I know what’s going on out here in real-job and I’m-so-important land. 🙂

Wow — you have the opposite experience of Laura above: teacher first, and then corporate America. So funny that you readily admit you’ve been “making it up.” Authenticity is a valuable trait as a teacher, for sure! The kids have Spidey sense when it comes to that, don’t they? 🙂

Great reading, perfect emphasis of the main points. I admit, I enjoyed it, despite the seriousness of the issues.

On 2): my kids come home from school and then they fight over who goes to bathroom first.

Hilarious. It’s the students’ plight, too!

This is brilliant… And these are most of the reasons I don’t want to teach anymore–even though I’m so good at it…

I really enjoyed reading your post and I totally agree with everything, including the last line about not leaving because of the kids.

I am about to leave the profession after 16 years. It really feels like a lifetime for me and I have been praying really hard, talking to so many people about whether I should go and looking at the students I have now as I take this very scary step out of the comforts of the classroom.

The reason for my leaving is that I have found something I want to focus on–teacher professional development. I have strongly believed in helping build teachers’ capacities to help them grow as educators. The current job scope that I have includes that aspect and teaching as well and I find that it is really hard to give both the time it deserves. As such, I am leaving a government job for one in a private institution to help develop strategies to build the capacities of all staff (non-teaching staff included). It has been a challenge making this decision but I have decided to take the leap, though I do not know if it will be a step in the right direction.

I think leaving this identity of being a teacher is essentially something very difficult to do, especially after being in the profession for a long time.

Oh, I definitely agree, Lynette: it was so disorienting to feel like I couldn’t call myself a teacher anymore. It’s something that gets into your being and is a part of your identity even after you leave. I wish you the best of luck in this next stage!

First, allow me to say that I am a high school English teacher, and I have also taught in Michigan. I currently reside in Florida, the reddest state ever.

I loved and loathed your article at the same time. I loved it, because you have accurately portrayed the teaching profession; and I loathed it because you accurately portrayed the teaching profession.

I teach pre-AP English, so I have left some of the horrors behind. Interestingly, we are nearing the conclusion of Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men…and my students are tearing up. Even the toughest of guys will cry at the end of that novella.

I have moments where I want to leave the profession, yet, I cannot fathom doing anything else. At the end of the day, I just close my door and teach to the best of my ability. I have found that after all the standards and benchmarks and infighting, that we the teachers, still know what is best for our students. We have chosen and studied education know what we are doing, and no what to do for these kids, and at the end of the day, that is enough for me. I, like many teachers, have to look ourselves in the mirror each day and know that we did what we thought was best.

Thank you for this article. I feel vindicated.

Compelling article; I’m also interested in both the very positive AND negative responses I just read on your blog. Obviously we are all biased based on our background and experience and those who feel teachers have no grounds to complain are equally deserving of their opinion. I wonder if they are parents of public school kids and, if so, how they have been satisfied/dissatisfied with their kids’ education. Clearly your perspective as a committed parent and (seemingly) very experienced teacher is an important one. I am also a teacher, parent, actor/writer; I have been teaching public HS. English and Drama at a “California Distinguished School” for 14 years. I have seen things change a lot in my district and trust they will continue to do so; ironically, as many things change they also stay the same. I feel fortunate (so far) that the push toward “rigor,” “data”, “measureable goals” and “informational material” has on balance not prevented me from teaching material that resonates with the students. Here’s hoping the powers that be don’t take us down dangerous paths ??

I was a bit taken aback by the negative responses, I must admit, though I expected some backlash and misunderstanding.

Teaching English and drama sounds like a dream job, and it sounds like you’re in a place you love! Keep on keepin’ on, Scott. You are doing important things.

I am in the process of becoming a teacher, and this did not dissuade me. I take that as a good sign. I figure that even if I get burned out on teaching, if I do it well it can open up other doors, as it did with you and your writing career. Mostly I wanted to comment and ask what hair products you use. Haha! No but seriously, I also have naturally curly hair and never stop asking people what that use if their naturally curly hair looks amazing.

Whew! I’m glad this didn’t discourage you — it was certainly not my intent, so, yay. And I love someone who can interject a little levity into a conversation, so let’s talk hair. When I wear it curly, I just scrunch in some mousse and use a diffuser until it’s mostly dry.

But let’s be honest: it’s in a mom bun 97% of the time. 😉

Wow! So glad I took the time to read that article! Such an interesting read! Thank you for sharing.

I will say, having you as a teacher in the very beginning of your teaching career was special. You really changed my perspective on how intriguing school could be. I’ll never forget you being a student teacher and then coming back when I was a senior.

At any rate, great blog! Congratulations on your beautiful family and I look forward to reading more.

Hi Heather! Thank you so much for taking the time to read and reply — your comment means so much to me. And congratulations on your new baby girl! She is SUPER cute, and she seems to be the light of your life. Welcome to motherhood! 🙂

Hello Melissa, I am a twenty-four year veteran physics teacher in Michigan and during the summer I go to Stanford University and teach for three-weeks a course named the physics of engineering. I once felt the same as you however, I decided to NOT let the administration, parents, students, etc. get in the way of what I was trying to accomplish in the classroom – turning out science-literate, critical-thinking citizens. Have I always been successful, not always – but when a student returns (emails, sends a letter…) telling me about the impact that I have had on them, I know that my efforts were not in vain. With that said, I however encouraged my oldest son to NOT become a teacher. Thank you for the blog!

Another Michigander/Californian! Thanks for stopping by. I can definitely appreciate your “nod, smile, and then do what I know works” approach. What did your son decide to do instead?

Mrs. Bowers,

As your other former students have said, you may not remember me, but I certainly remember your class. It’s interesting to hear what went on behind-the-scenes while I was preoccupied being an oblivious 16-year-old….

You were one of my favorite teachers. I looked forward to your class and I took a lot from it. I have always felt that I don’t have a creative bone in my body. I appreciated some of the activities from your class that encouraged that part of me; I loved working on my snapshot journal and reading works by E.E. Cummings. Also, part of my current job entails GED preparation, and I can still recite my list of helping verbs when needed You also encouraged me to take an AP language art class the following year, which I declined to do because I lacked the confidence. However, I decided to take an honors writing class in my freshman year of college, finally deciding to listen to the guidance of others. I want to thank you for all of these things. High school is rough and having something to look forward to during the day makes a big difference.

I hope issues such as these don’t discourage future educators. I hope and pray that my future kids have teachers like you!

Courtney (Phillips) Palen

How wonderful to hear from you, Courtney! I remember you (and your brother) very well, of course — although your new name threw me off for a second. Congratulations on your marriage!

Thank you for sharing so many awesome memories from your time in my classroom. It made me smile to read each one (those helping verbs NEVER leave your brain, right?!). How wonderful that you decided to take an honors writing class in college. Surely you excelled; you were such a bright, earnest student, and your incredible work ethic is still serving you well, I trust. 🙂 Thank you so much for taking the time to leave a comment! Please keep in touch!

After 9 years of teaching high school, I left the profession 5 years ago. I work in corporate America now. I miss teaching very much. I miss my students and the creativity that came long with the profession. My colleagues tell me things got much worse now than they were 5 years ago in terms of things you covered in your article and other factors (I worked in a state-controlled title 1 school where state-control just got tighter.)

I don’t know what to do with my professional future. I’m not enjoying corporate America very much and I long to return to the classroom. I also live in California now and am not certified here. Also, I can’t afford to be a teacher here due to high cost of living. Maybe this is the universe’s way of telling me to not return to teaching? Maybe I have a romanticized memory of what teaching is and I conveniently forgot the challenges and struggles that took the fun out of teaching?

Thanks for taking the time to write this article.

You’re totally right — I haven’t researched exactly what we’d need to transfer a certification to California, but it’s undoubtedly a bit of a process. Maybe we’ll both find our way back to the classroom one day! But in the meantime, I sure hope corporate America starts treating you better. Thanks for taking the time to add a comment!

Hello Melissa,

I taught secondary English/Language Arts in Michigan for 19 years before I resigned. I was five years from retirement when I just could not take it anymore. My doctor told me the stress was killing me. You see I was a good teacher. Administrators admired my classroom management. Parents requested that their children be put in my classes. These are good things, right?

As you and other teachers know, teaching is a profession where you are penalized for being good at your job. You are given the toughest students because you can handle them. You are given the apathetic students because you can reach them. You are given 3, 4, or maybe 5 different types of classes to teach because you can handle all the extra preparation. You are assigned to endless committees and asked to mentor new teachers because you have such a wealth of experience. You ARE until you CAN’T anymore.

I had seen 5 teachers in my building suffer hear attacks, and that fate was awaiting me.

I also left because of the increase in threats and violence towards teachers (including myself). These attacks came from both students and parents. My student teacher was stalked by a parent. A teacher in my building suffered a concussion when she was head-butted by a student. I had to confront a parent who had come on campus with her adult daughter to “talk to” a girl her other daughter had a dispute with. The assistant principal was punched in the face. The last straw for me was when a six-two, 210 pound, 17 year-old in my freshman English class charged at me because I asked the class to turn in a homework assignment. I avoided his fist, but was told “off the record” that I should have let him hit me because then he could have been expelled. The suburban middle-class high school I loved had become an unsafe and hostile environment in which to work.

I missed the students terribly, so I started teaching part-time at the community college level. This means my income was cut to less than half of what I was making, and I have to pay for my own health benefits. But I’m alive and healthy and I still do what I love.

This is a good article, the sad thing is the only people what will read it and take it to heart are probably the people already in this profession hahaha

I have run and built the entire ICT syllabus for grades 1-7 and I teach the classes and I run the network, for 12 years now. My girlfriend has been teaching classes of 40 kids for 10 years now and we’re both done. We’re tired of people acting like they’re in charge of us teaching when they know nothing about it. So that’s okay, I’m going into corporate and it’s great – waaaay easier and less pressure.

Let the difficult parents teach their own kids, let the whole thing come tumbling down and lets see what happens because no one will want to do it anymore – at least not where I am from. Since our jobs are not “real” jobs lets leave the profession and go elsewhere

I have to agree with you. Teaching has done some great things for me, and has allowed me to live all over the world. The fact is though that education is run by governments, and it is way too simple to have that many people try to influence it.

When I plan a lesson, I ask myself what the kids need to know or be able to do. Then I work out ways that I can help them to learn those things. A day or two later, I go and teach the lesson, adapting it as I go in accordance with the response of the children.

That’s it. That’s all there is to it.

If I could spend less time documenting everything in a way that someone else finds useful, and less time ensuring that I can prove that every last moment of each lesson has taken place in the way that I described it would at the beginning, then everyone might get a little bit more out of the experience.

Of course everyone knows how they would do your job better than we do. They would all probably take different approaches to it. The fact is that we would probably take different approaches to it as well if our hands weren’t tied by whatever new ‘initiative’ some government type has just come up with to justify his job.

The problem is that for all the training that we undergo before we start, and all the in service training that we find ourselves doing, we are not trusted to the job for which we are employed, so we are made to dance like puppets, and deliver the blandest and most pointless lessons to our students, so that we are all doing the same.

The individuality has been sucked out of the profession (worldwide), and it will now, sadly, only attract the blandest people.

I’m leaving teaching after 24 years. You’re spot on. I didn’t get into teaching to raise tests scores.

I have 26 years in and I want to retire NOW. I have lost the passion, the drive, the desire.

I happened to google “7 years left of teaching” and found your post. I’ve taught in California and Michigan. I have 7 years until I retire. Despite being a scrappy, hard working, strong willed woman, I’m not sure I can make it.

You hit the nail on the head.

Hello Melissa,

I’m Michigan, born and bred. I was racing through your article so quickly that, had this been your class, I’m sure that the essay on the aforementioned would have been a disaster. However, there was one section that really caught my eye. It was “Number 7.” Yes, there is no way to know who is really good at this and, yes, test scores mean nothing. The best teaching I have ever engaged in had nothing to do with mandated curricular content. In fact, I was so good with so many types of kids, that all the counselors and all of the special education teachers decided it was the best idea in the world to send all their struggling students to my class–and I welcomed them. I wanted them. I rolled out the proverbial red carpet for them.

We began making huge, HUGE progress with the kids who needed it the most and, naturally, with a challenging population the test scores weren’t all that hot. The other history teacher in the building had 17, 21, 26, 19 kids in his classes. Only the top 10% of kids wanted his class. It was hard, and he was hard-assed. Great guy, hard-assed. Mr. Bruce’s class, on the other hand, was warm, welcoming, and he (me) spent time after school making sure that the special needs kids got a different test, or read the test to them, etc., etc., etc.

And yet, the brilliant, 4.0 students took my class, too! Yes, some of the most brilliant kids I’ve ever met loved my class. The Associate Principal walked up to me in the hall one day, and said “Robert, you wouldn’t believe what my son Scott says about you when he comes home. In fact, he comes home, and your class is ALL he talks about. He says that you’re brilliant, you’re funny, you’re caring, and kind, and he says you know EVERYTHING!!! One day he came home, and couldn’t believe that you understood and explained how the atomic and hydrogen bombs worked, and the physics teacher COULDN’T. He says you never lecture with notes, and that there is never a question you can’t answer…he wonders why you’re not a professor. He just loves your class, and most of all he adores and respects you so much!”

Of course, I was floored. Scott was, quite easily, the most brilliant history student I’ve ever had. In fact, his only competition was a young woman in my fifth period that same year whose grades were just as good–she just had to work a little harder at it. Brilliant kids, both of them. Truly, I was floored.

“Angela, I don’t know what to say…I mean, I just have a passion for my subject, and the kids are fabulous. And of course Scott is…well, you know what a brilliant young man he is. He just…”

She burst in “We are so lucky to have you, Robert. All the kids, I mean ALL the kids relate to you and just love you. You know, Scott said to me the other day ‘You know, Lisa would have LOVED Mr. Bruce’s class!”

Lisa was Angela’s eldest daughter. She was on scholarship at Harvard when this conversation took place.

I was still basking in the glow of this moment–the kind of moment that real teachers live for–when I was called into the “big boss’s” office.

“Bob” (Please don’t call me “Bob.” I’m not Bob, and I’m not your friend)…”Bob, I think that we have a problem.”

“Really? What’s going on?”

“Well, your test scores aren’t…well, they just aren’t very good.”

“Well,” I said “When you have a common assessment at the semester’s end, and the “lead” teacher (Mr. S–ts) writes the test, and he has the top 10% of kids academically in his class, it’s kind of difficult for my kids to keep up, especially when I’m maxed out at 30 kids in every class…and he has, what was it? Twenty six was the most he had in one classroom this semester? Yeah, well, it’s kind of hard to match his outcomes. You know, top 10%, he writes the test, fewer students. I have all the Special Ed kids and kids who struggle academically, etc. Do you really think that I can bring all of my kids’ test scores up to Mr. S–ts’s classes?”

The big boss waves this off as if I didn’t say it. “So, try and imagine that you’re Mr. S–ts for a moment…how would you teach your class?”

“Ummm, look, I’m not Mr. S–t. I don’t teach like Mr. S–t. I don’t want to be a teacher like Mr. S–t. And I think making that kind of comparison, especially given the amount of hard data about the demographic differences in our classes ought to clue you into the fact that you’re comparing apples and oranges. In fact, my test scores have come up over 30% over last year. That’s a lot of improvement, if you believe in that sort of thing…”

“Yes, well, the State is going to be evaluating you on those test scores next year, and me, too…”

“So, is that what this is really about? You’re about to, obliquely tell me that those test scores need to come up, or else…even if I have to teach to the thing.”

“Oh…well, no, not like that. But, you know, in a way…we all REALLY teach to the test, or teach for the test.”

“No, actually I don’t. I don’t teach to a test. I don’t even teach history. I teach students…you know, young people? Our actual customers?”

“I don’t think I like your tone, Bob.”

“What does my tone have to do with you telling me, without telling, me to teach to the test. And don’t call me Bob. It’s Robert, or just Bruce.”

“Look you have an obligation to teach in the way I have prescribed for you, and to get those test scores up. Maybe you don’t understand the gravity of this.”

“Yeah, boss, I think that I do. You and the other administrators are scared that the State will breath down your necks about test scores, and yet you’re doing nothing to make classes equitable in terms of numbers, demographics, or any of the objective measures that would be commensurate with making those test scores just about equal with Mr. S–ts’. You know that! If you want higher test scores across the board, why don’t I GET to write the test, since S–t has all the other factors that lead to test success on his side? And how about he gets 30 kids in some of his classes, instead of having me maxed out in every period?”

“Well, he’s the lead teacher, and you’re the new guy…”

“Look, I know what this is really about. It’s really about the fact that I teach differently, and the kids like it, and you can’t stand the fact that…”

“Well, you waste a lot of valuable class time teaching things and talking about things that aren’t going to best tested. If you would just get on board with the…”

“GET ON BOARD? With WHAT? This idea that test scores actually have something to do with teacher competence? What you’re suggesting, and have been insisting upon throughout this insulting conversation, is that I teach to the test, in fact you want me to CHEAT, and then that will make me look like a ‘really good teacher.’ I think what makes me a really good teacher are the very things that you’re denigrating right now, and most of the administrators and teachers in this district agree with me.”

“IT DOESN’T MATTER!” He was really agitated now, “You have an obligation to do what you’re told. And I’m telling you that you need to teach in the manner I’ve described, and those test scores need to come up.”

At this point, I was devastated, but I wasn’t going to let this prick know it. I knew when I walked out of his office that my days at this school were numbered. I’d worked most of my adult life to be this kind of teacher, and for years had had glowing, sparkling reviews of my work, and then suddenly the world of education took a turn down a dark, dank, and frightening road. I was a zero in the world of test scores and bureaucrats, no matter what my kids, their parents, other teachers, or even other administrators thought.

So, half way through the year I had a “nervous breakdown,” and never went back. I negotiated a settlement with the district, and only went back the next August before school started to clean out my room. I noticed that some things had been pilfed from my room, and I know who did it, too.

Angela was there, waiting to let me into the school and into my room. She gave me a big hug as I came in the door. I packed up my stuff, and got out as quickly as I could. She gave me another huge hug as I was headed out the door.

“Scott says ‘hi’ and he feels really bad that you weren’t able to finish the year. The kids were confused.”

“Yeah, and there was no way we could have told them the truth to unconfuse them about the situation, could we?”

“No, no we couldn’t.”

“I’ll miss teaching, I’ll miss this place, and working with you. Please give Scott my best. It’s been a great part of my career, Angela.”

“Take care…this is so unfair.”

“Yeah, well, right now, as much as I have loved teaching…I wish that I’d gone to medical school like I’d planned.”

And that was it. I never taught another class. I was too old to go to medical school, I’m now getting my MSW and will be an LCSW/LMSW soon. I miss teaching history, my great passion in life. Most of all I miss the kids. But I don’t for a second regret leaving when I did. Education has become a wasteland, and I didn’t want to be around when Big Brother and the Holding Company decided to come ’round and really put the smack down on us all.

Now, everyone in that district has an exit strategy. Everyone wants out. And last time I checked, the numbers of young people entering teacher education programs dropped 38% from 2010 and 2014. In four short years, 38%.

Tell me, Melissa, tell me…I wasn’t the greatest teacher in the world, but I was darn good one. The story that I just told you is 100%, no BS, true. Where are they going to get people like me as salaries drop, tests get dumber and dumber, benefits are slashed, and teaching is more and more of a mechanical exercise than the art it used to be?

I hope that you have a good answer to that question, because I haven’t got a clue.

Thanks for reading this, if you made it this far.

All the best,

Robert Bruce

PS When I went to my mailbox, I found several dozen letters from kids who were either thanking me for a great “half year,” or announcing that they “had [me] for the coming year.” I was crushed by the latter letters. It still hurts.

I’m a first year teacher and have experienced a much more difficult year than I had even imagined… knowing full well that teaching can be an emotionally and physically draining career and first year is a whole other ball game. I have spent countless hours crying and confused about whether this is the right career choice for me. Wondering if there is any wisdom for those who do choose to leave early?

Oddly enough, this post came up when I searched for “I don’t want to teach again but I need the money.” In my state, teachers in or near big cities get paid well. In lower socioeconomic districts, you get paid even more – “hazard pay” is what I call it. For 10 years, that’s where I was, in a freshman English class. Loved the content, loved the IDEA of what teaching is supposed to be. The reality wore me down over time. The teaching to the test, the data-driven decisions, the threats that teachers needed to change grades to lower the failure rate, the principal I had for 4 years who had it out for me (no idea why) and walked the fine line between illegal and legal actions against me, and admins who refused to back us up. I was stuck. Recently divorced with a mortgage and terrible credit, I was literally stuck. I was depressed, suicidal with 3 attempts, and resentful. I needed out, or I was going to end up dead. Somehow, I was blessed with a windfall of a bank account I didn’t know I had, set up by my grandparents when I was a kid. I used that money to quit, move out of town, and go to school to get another bachelor’s in another discipline, with the intent of going into a new career field. Well, I graduated, but the job offers weren’t happening. Money was running out fast. My parents’ advice: I had to go back to teaching, (FWIW: my therapist, my psychiatrist, and my medical doctor told me to do anything BUT teach.) But I filled out applications all over the state; anywhere but where I came from. And I cried each and every time I filled them out. I don’t want to do it. I have insomia and, when I do sleep, I have nightmares about being in a classroom. My stomach hurts almost all the time. I went on my first interview yesterday and I will find out tomorrow if they’re extending an offer. I’m sick. Literally sick. Food won’t stay down and, if I haven’t eaten, I just dry heave. This is the last thing in the WORLD I want to do, but I absolutely have to have the money. Once again, I’m stuck. My advice to people who are on the fence about teaching: if you’re planning on teaching a core subject, find another career path and major in something else. But, yes, I do miss the kids.

I have been a high school history teacher in Phoenix, AZ. for 32 years. I began at PUHSD right after college at the age of 21. They gave me a class of seniors! It was the best class ever,….right after Regan was shot and in the middle of ugly gang wars in the district. I loved my job up until I turned 47 . However the joy I felt every day going to work and showing the kids the beauty of history and what you could learn from the stories kept me going, Those kids were so receptive.

However, ultimately even after I had accrued my 80 points I kept teaching for two more years. My colleges thought I was an idiot. When I walked away I knew it wasn’t because of the kids and their cellphones or the unresponsive parents or those who just blamed me. It was because of the politics and the b.s. that I had to suffer through because someone else said they knew better. I know that I changed a bunch of lives and I love that, but to this day, and yes I did participate in #redfored wholeheartedly, I don’t believe anything will change in AZ education. Too many politicians who disservice us, too many parents who have much more things on their minds ( immigration issues) I’d still be teaching at Alhambra High School to this day if it wasn’t for the damn school board, testing, and the state. Someday, they will be sorry I am gone.

I couldn’t agree more. Get rid of phones, google, computers (go back to Libraries and Dewey Decimal System!) and maybe I will stay…Otherwise, forget about it

Man. I’m a new teacher (only year 4) and I’m already starting to feel burned out. Part of it is not being able to stay at a school for more than 1 year, but a bigger part of it is just the weight of the disrespect I face daily. Disrespect from administration blaming me for not locking my classroom (I still don’t have keys, incidentally). And who tell me that it’s my fault the kids got into a fight, because my lesson on unit rates wasn’t engaging enough. As if student engagement suddenly makes a boy not break up with you and start dating your best friend.

Disrespect from parents who want to know how I “let” their kids fail, despite me cajoling him and begging him just to take out his notebook each day and simply listen.